At a culture's pole of maximum abstraction, it is intelligence liberated from utility, and therefore intrinsically experimental. Where such speculation probes the limits of perception specifically, in art, it is fated to run up against the edge of time, whose sense nests all others. It is this, which eternally binds apocalypse to art as a particularly evocative and even paradoxically popular source of intoxication. The desire to depict the unimaginable happening is the abstract motor of novelty in the cultural domain. What apocalyptic art aims to attain is a maximum vulnerability to be afflicted by the alien sovereignty of whatever constricts the world into shape from without.

The basic unit of an apocalyptic pedagogy, the smallest particle that can distinguish one future from another, is the omen. Omens are what sensation finds when it plunges deeply into what is contemporaneous with it and feels around for inscriptions of the future embedded therein. Frequently this takes the shape of an identity between trends and traditions as maintained courses of fate. Apocalyptic art obviously falls into this pattern in and of itself. More urgent is how conception of a metaverse necromantically reboots a cyberspace that had been laid to rest in the same hype-crypt as the Sikh idea of persons being the theater masks of arcane entities staging a play, Zhuangzi’s butterfly dream, and all the more unfathomably ancient incursions of hallucinatory immersion upon reality. Accordingly, the spectral entities that are once again emboldened to crawl out of this tomb are of now best named as 3DCGI avatars.

Woodcut of typical omens in the Nuremberg Chronicle.

The importance of 3DCGI to cosmogony is already evident from the fact that it enacts the machinic spawning of a local atoll of space and time. Where it transgresses into the mire of religion, and particularly religious literature, is by accessing the same burn-core of sacrifice these had previously touched upon: identifying worldbuilding with a melting of the substrate upon which this very computation happens, tangibly rendering cognition an “organon of extinction”, as Ray Brassier first put it in Nihil Unbound. It comes down, ultimately, to a maximally abstracted art of metalworking that yields a singular adherence to the occult splinter of futuristic speculation: the creation of reality is exactly identical with its disintegration.

Gustave Doré, The Flood.

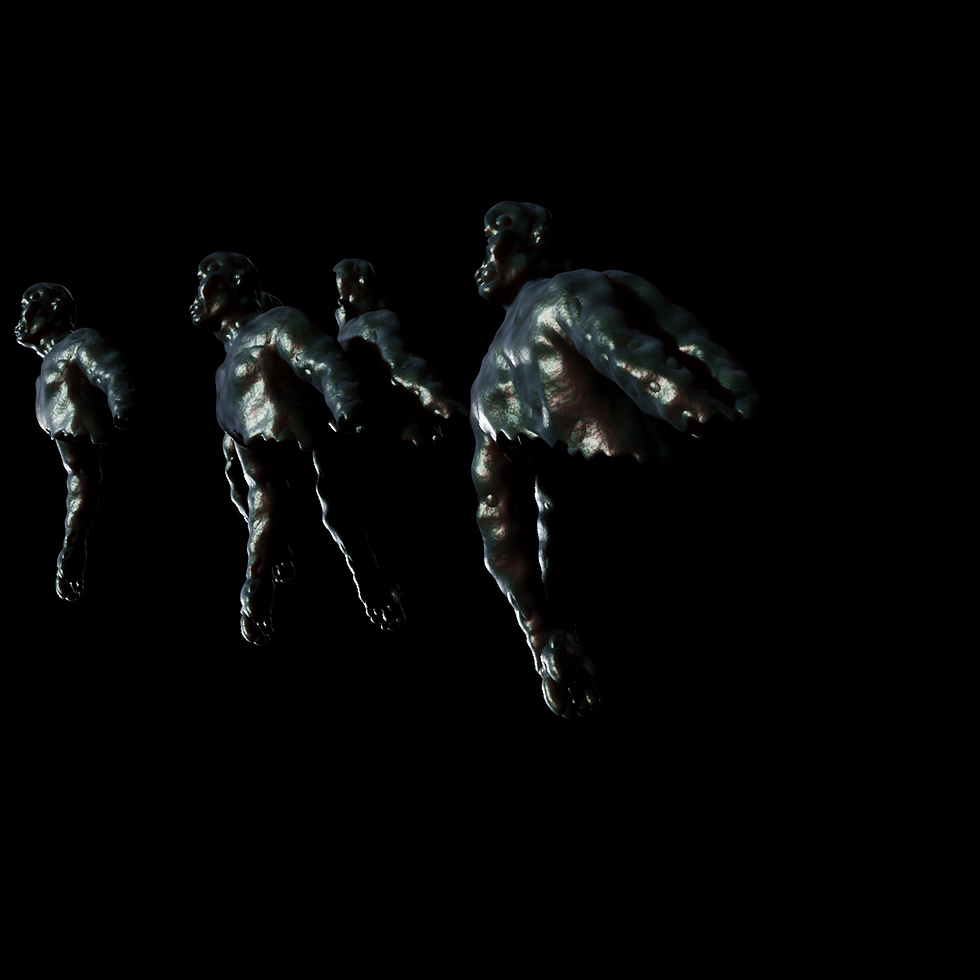

Metals, glistening with the caustic thin film iridescence of oil slicks or alien shellac, and exuding miasmatic smoke plumes into outer night, are the substances that inspire The Flood (Logorrhea) to latch onto, but also satirize the dramatic narratives – whether comic or tragic – that are employed to frame the deep and unknowable rhythms of cosmic abstraction. Among the things the series aims to melt down in this attempt to radically modernize this traditionally Gothic medium of metal is the usually implicit intermedial communication established with language that is inherent to naming a piece of art. To this end, thermal hardware diagnostics are subjected to the qabbalistic method of finding linguistic fragments that – when numerized according to a particular principle – reproducibly coincide with the value at hand, explicitly tasing out the poetic capacity of material deformation. Sense itself is envisaged as a system of melting slag always already in the moment of being expended with.

While the name of the series itself refers to the ambient anonymity that comes naturally to computer-generated images and the open source environments that facilitate so many of them, this is also why it partially takes its name from a print by French artist Gustave Doré. The Flood, created during the same time as his renowned illustrations of Paradise Lost, shows the aftermath of something intolerable having flooded in to leave the world liquefied. The image of disaster is of clear relevance to the exhibition’s linked themes of intelligence explosion and ecospheric devastation, as well as my approach to these (which is rather the path by which they reach me).

Yet as the paradoxical depiction of a sight after the end of time, Doré’s print also depicts how with everything having flown out of hand, things begin to cluster together in unanticipated configurations and a spontaneous order emerges from the violent movement of dissolution. In this way, it serves as a pretext for adopting a semiotic practice of displacements and debriscollage: replicating warped bodies along curved paths to model terrestrial history as a going forward in circles.

Comments